Leaderboards showing the best performing models (Vellum LLM Leaderboard, OpenASR Leaderboard). News reports stating the latest model from company X is ‘better’ than Y (BBC News on DeepSeek vs ChatGPT). Or a company deciding whether their AI-powered product is ready for release (Claude 3 Release). All of these have one thing in common – a score has been given to the AI model.

In this post, I will describe model benchmarking, and importantly I will outline several reasons why we should not always take results on benchmarks as gospel. The next time you see reports of a new model outperforming all the others, you may just question how true that statement is.

Motivation

How can we be sure that a model will do well in the real world? And importantly how can we decide which model performs better than another?

Researchers and developers spend lots of time building models within their infrastructure (jargon for describing the computers and networks). They use datasets they have created and algorithms they have designed. However, an important final step of the AI design process is to predict its real-world performance.

So How Is It Done?

How are models evaluated? Why is dataset curation challenging? And what has the community done to overcome these challenges?

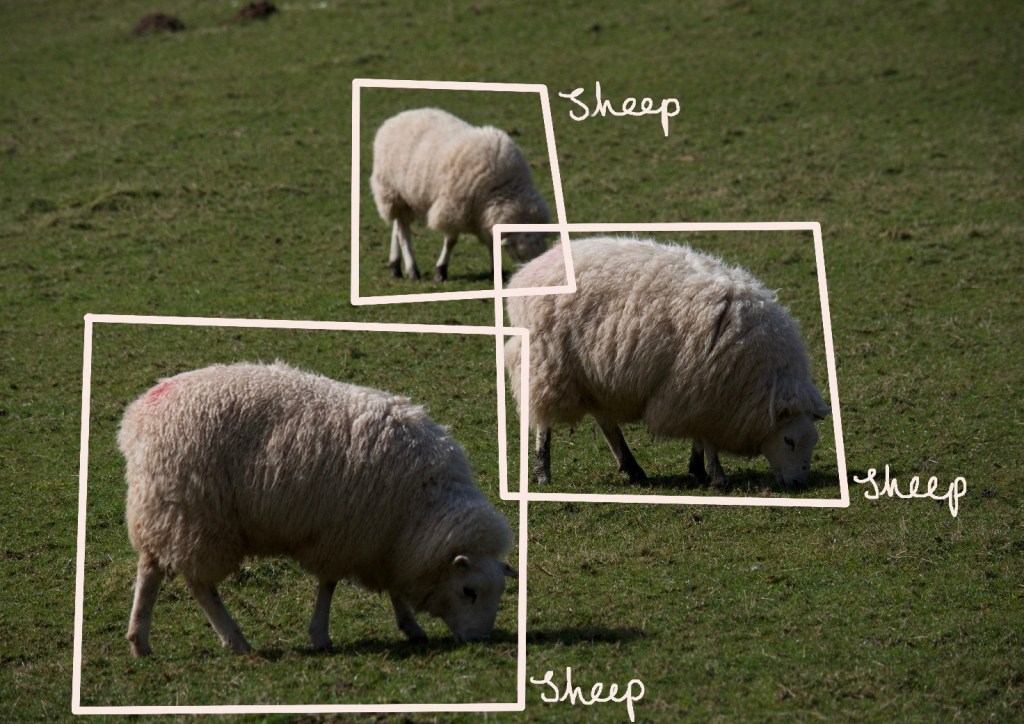

For many projects, researchers will have a collection of correctly labelled items. This could be labelled images (ImageNet), correctly transcribed speech (LibriSpeech) or correctly answered exam questions (MMLU).

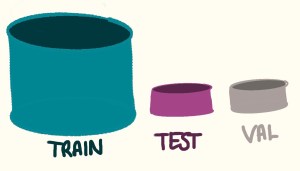

The researcher will typically split the collection of suitable data into three parts. The training data is given to the model to learn from. The validation data, which is be used during development for intermittent testing. Finally, the test set is for the final quality check.

Alongside the evaluation data, a researcher needs to define metrics. A metric is a way to measure the score of the model on a task. We will revisit metrics in more detail in a future post. For now, think of the metric as an accuracy score. How many did the model get right out of all times it was queried?

A metric is a word used to describe the scoring method of a models performance.

Typically when a researcher decides on the final model, they have found a model which does well on the exam they have set, using a marking criteria they have set. They measured the performance of the model against the test and validation datasets. The more correctly labelled examples to test the model, the more confident you can be in the model’s performance. Under the caveat that these examples represent what the models will see when published!

However, there is a trade-off. Labelled dataset building is costly and time-consuming. Imagine if you are building an automatic phone call transcriber. You’ll have to manually transcribe thousands of hours of audio – this can’t be done quickly. Because of this, the research community has evolved to publish and share datasets. These are such valuable resources, and I’m certain the rate of AI development has been enabled, in part, by these open resources. These shared resources for evaluation are often referred to as benchmarking datasets.

Extra Resources for those who want to learn more…

There are so many datasets available on the internet for anyone to use – have a look at my favourite resource HuggingFace datasets. Google has created a huge language benchmarking dataset called BIG-Bench. To achieve this scale, they have leveraged crowdsourcing to encourage the contribution of this massive dataset across a huge number of tasks. LiveBench, as mentioned earlier, is another awesome benchmarking resource built by Abacus.ai. It is also aimed at language models, and continually releases new questions to maintain relevance and prevent contamination.

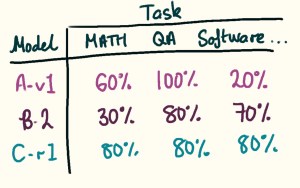

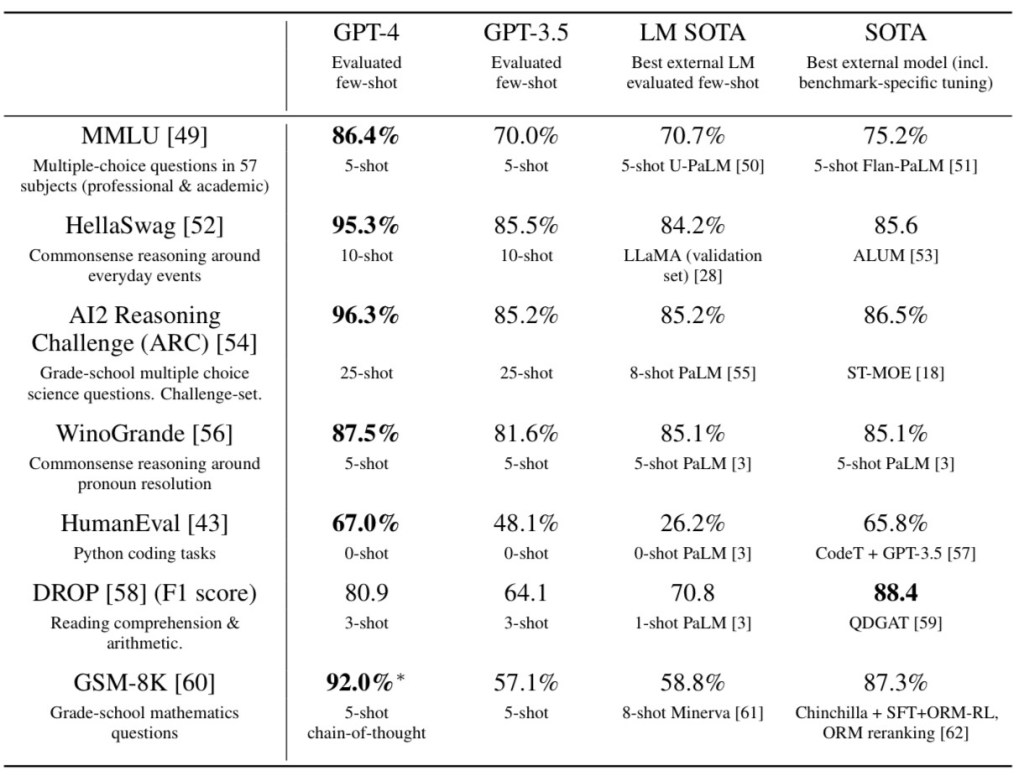

It has become standard practice to run a new model against common benchmarking datasets. When the model is released, typically an academic paper with the results on these benchmarks is also released. This helps the community how their model performs with other state-of-the-art models. Testing over a range of tasks, such as the Table below from the GPT-4 Technical paper, can highlight weaknesses.

A Word Of Caution

It sounds great right, we can compare models under similar evaluation conditions – surely this is enough? TLDR; The quality of the benchmarking results depends on several factors; choice of metric, inclusion of test data in training data, quality of the test data and publisher bias.

Unfortunately, it is not that simple. Although I am in no doubt that benchmarking and comparing models this way is extremely valuable, I want to share some words of caution for you to bear in mind when hearing about new model releases.

Choice of Metric

As I eluded to earlier, choosing a metric for evaluation on a task can be difficult. Particularly in the realm of language models, where the answers are free-form text, not just a box around a cat in the picture. I will explore this more in a future post. Think about how a teacher marks a writing exam. Several students in the class come up with answers to the same question. Let’s imagine all the answers are deemed correct by the teacher, but when compared word for word the answers look completely different. The teacher will have a marking scheme and will use their professional experience to subjectively mark the students.

This is a challenge the community faces when designing metrics for language models. How can we come up with a programmatic way of modelling a teacher marking homework?

Researchers have created several metrics which try to do this, BLEU and ROUGE are some examples. But these techniques essentially compare the existence of specific words or phrases with respect to a reference sentence. They do not take into account writing style or coherence. They have been shown to not represent human judgment well. Model-based evaluation, such as G-Eval, is one solution. This is an approach where a larger, more capable model marks the answers of a smaller one. But more on that another time…

Inclusion of Test Data in the Training Data

Companies create their models in their infrastructure. The outside world won’t know which data is used for training the model. Benchmarks are publicly released. Training is done in private. Because of this, we can’t know for sure that examples from benchmark datasets haven’t made it into the training data.

The phrase ‘training the model’ describes a process. Researchers use example training data with correct answers. They use this data to build a model.

If examples from the benchmarks are in the training data, then the model has seen the answer before. Imagine a student has seen the exam and the answers during their revision period. They are more likely to get these answers correct than they would have when presented with an unseen question. Any scores given to a model against questions it has already seen will be higher than its true ability. The model will look good in the tables in their academic report. However, it might feel worse when a user comes to test it.

The addition of the test data to the training data may be intentional. However, examples from one benchmarking dataset may be accidentally duplicated and included as part of the test data of another.

A challenge we have is that we don’t know for sure how the model was trained. Even if the companies are transparent with their training process – we should still be wary. Ultimately first-hand testing, by humans, is the real test.

Quality of the Test Data for the Target Task

The most critical challenge is determining if the data used to test the models truly represents the application. This application is the one in which the model is used. The end user, and how they will use a model, should be considered throughout the design process. Perhaps the model is being used for a very niche task, in a very particular well-understood environment – such as assisting medical scan analysis from a specialist imaging scanner. With sufficient time and money, the researchers could create a very representative test-only dataset and get a good idea of true performance.

Unclear or open-ended end-user applications, like the all-purpose chatbot (ChatGPT, Claude, DeepSeek) may be used for many different tasks, by a huge range of users. Every user will have their way of interacting with the model, with their own vocabulary and language style. Capturing these nuances in a dataset is not easy. Paired with the inability to properly evaluate long-form text, I believe the LLM benchmarking can give you a baseline understanding of ability – but the only way to measure its ability in a specific task is through targeted human testing.

Publisher Bias

The academic world can be very competitive. To gain wide interest in your work, unfortunately, attention is mostly given to those approaches surpassing the leaderboard and becoming the ‘best model’. This may subconsciously persuade authors to share only their best results. The evaluations must be validated by an independent body.

Conclusions

Double-check metrics, and double-check evaluation datasets. Do these align with your expectations of what the model needs to be able to do? And always try for yourself.

Benchmarking datasets are a great initial resource for understanding model performance and comparing between models. The community has done so well at making these resources free, and available to all. They are valuable assets and a valuable step in AI model development.

However, I hope this post has outlined several reasons why you shouldn’t always trust what you read!

Double-check the metrics you see discussed, and check you understand what they are measuring. Decide whether that corresponds to how you would mark the answer. I will be following up on this topic, so stay tuned!

Unless the test datasets exactly match the target application, then I encourage you to take the scores with a pinch of salt.

Unless the results have been independently reviewed by a different group, then I would be wary – and probably try to evaluate myself!

At the end of the day, the best way to understand performance for you is to test it yourself!

Leave a comment